Fantasy meets reality: Western Highway Buangor to Ararat

In 2020, I reviewed the economic appraisal and crash history of the Western Highway in Victoria. I did this to help those making legal challenges to the Western Highway Upgrade project and its effect on sacred cultural sites between Buangor and Ararat. They’ve now agreed that I can post my findings for wider reading. This…

Melbourne Airport Rail: a patronage discussion

When Melbourne Airport Rail opens, and even if air travel resumes its pre-COVID growth, the trains could be less than half-full at the busiest time of day. SkyBus and airport trains together could take one-third of journeys to and from the airport. This is a high mode share by Australian standards, but continued growth means…

Infrastructure Victoria’s 30-year strategy: confusing and incomplete

Infrastructure Victoria’s draft 30-year infrastructure strategy is confusing and disappointing. It needs to embrace much stronger commitments to change. We must urgently eliminate harmful emissions and rein in our ecological footprint; IV’s strategy will not help us achieve this.

Induced travel: how quickly do people adapt?

INDUCED travel due to changes in the transport network is a well-known phenomenon. For many years, it was ignored in transport modelling, by accounting only for re-routeing of trips rather than mode shifts or origin and/or destination changes. Nowadays, most modelling includes it, thus producing variable trip matrices between scenarios rather than fixed ones. A…

North East Link – the perfect storm

North East Link is shaping up as the biggest mistake of the Andrews government’s autocratic approach to transport infrastructure.

It has many problems that will eclipse those of the West Gate Tunnel.

The taxpayer will take the risk of its failure to attract traffic, and it’s not worth the massive impacts on the…

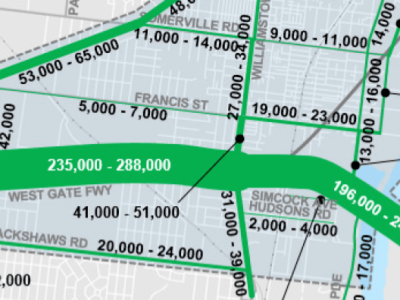

Tunnel Tales (3 of 3) – Rubbery figures: why the West Gate Tunnel doesn’t stack up

The West Gate Tunnel doesn’t stack up and it should never have been approved. Its economic benefits were overstated in the business case. Rather than $1.30, the project will probably return only $0.60 per dollar invested. It doesn’t stack up financially either. Transurban needs $2.6 billion from the public purse, plus more toll revenue from…

Tunnel Tales (2 of 3) – transport modelling and the ‘single loop’

Transport modelling for the West Gate Tunnel was not done to prescribed standards. It contains illogical methodology and errors that probably resulted in significant over-estimates of future traffic on the project. It also can’t be shown to be mathematically stable, which is a fundamental requirement of such modelling. It therefore shouldn’t have been used for…

Tunnel Tales (1 of 3)

The Government’s assessment of the West Gate Tunnel contained significant errors in the transport modelling and the cost-benefit analysis that made the project seem a lot better than it was. It should never have been approved, and I predict that when it eventually opens it won’t deliver the claimed benefits.

Victoria’s broken transport planning ‘system’

Let me be very clear about this – the system of rational and objective planning for transport is completely broken in Victoria.

Politics has trumped planning, and there’s no guarantee that the chosen investments are the right ones.

It’s nothing short of pork-barreling in the extreme.

First post – what’s this all about?

WELL, this is the first post to my blog! Welcome to all readers. I’ve decided to start this site as a place I can post articles, analyses and commentary on transport planning and my experiences. Some posts will be topical and current, while others might go back in history and highlight some particular projects, studies…

Follow my blog

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.